Introduction

There are four essential modules, which are required to do any editing at all

prosemirror-modeldefines the editor’s document model, the data structure used to describe the content of the editor.

prosemirror-stateprovides the data structure that describes the editor’s whole state, including the selection, and a transaction system for moving from one state to the next.prosemirror-viewimplements a user interface component that shows a given editor state as an editable element in the browser, and handles user interaction with that element.prosemirror-transformcontains functionality for modifying documents in a way that can be recorded and replayed, which is the basis for the transactions in thestatemodule, and which makes the undo history and collaborative editing possible.

1 | import {schema} from "prosemirror-schema-basic" |

Transactions

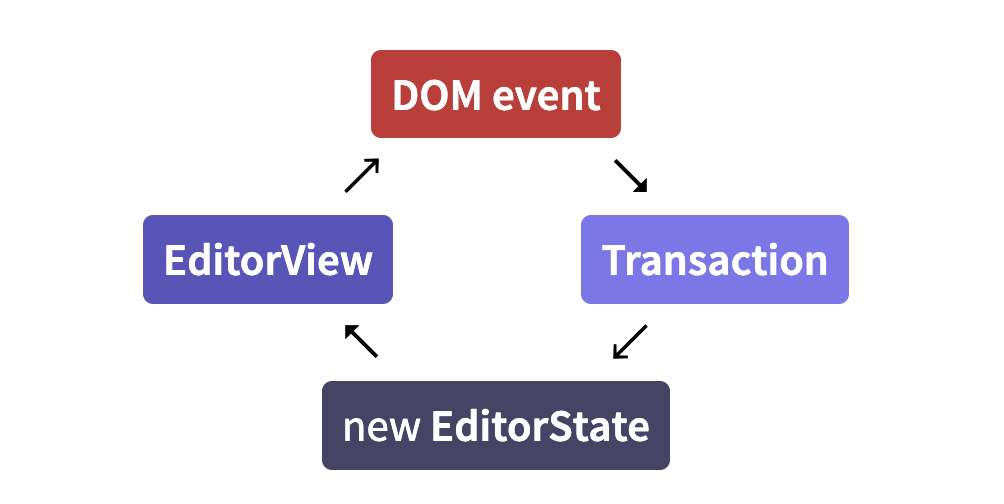

When the user types, or otherwise interacts with the view, it generates ‘state transactions’. What that means is that it does not just modify the document in-place and implicitly update its state in that way. Instead, every change causes a transaction to be created, which describes the changes that are made to the state, and can be applied to create a new state, which is then used to update the view. By default this all happens under the cover, but you can hook into by writing plugins or configuring your view.

Plugins

Plugins are used to extend the behavior of the editor and editor state in various ways.

Command

Most editing actions are written as commands which can be bound to keys, hooked up to menus, or otherwise exposed to the user.

Content

A state’s document lives under its doc property. This is a read-only data structure, representing the document as a hierarchy of nodes, somewhat like the browser DOM. A simple document might be a "doc" node containing two "paragraph" nodes, each containing a single "text" node.

When initializing a state, you can give it an initial document to use. In that case, the schema field is optional, since the schema can be taken from the document.

1 | import {DOMParser} from "prosemirror-model" |

Documents

structure

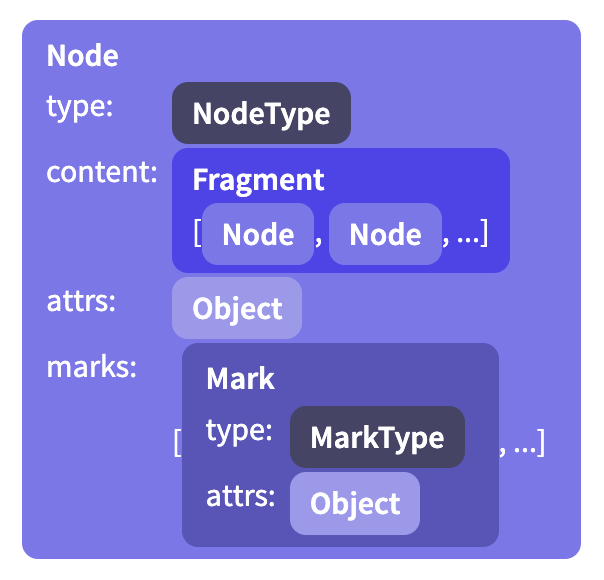

A ProseMirror document is a node, which holds a fragment containing zero or more child nodes.

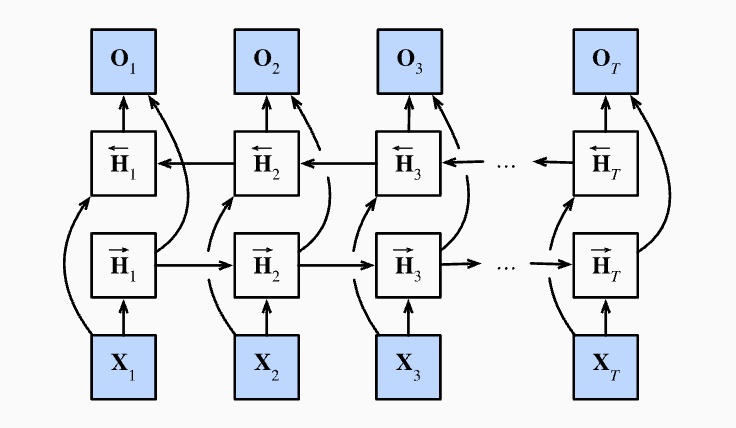

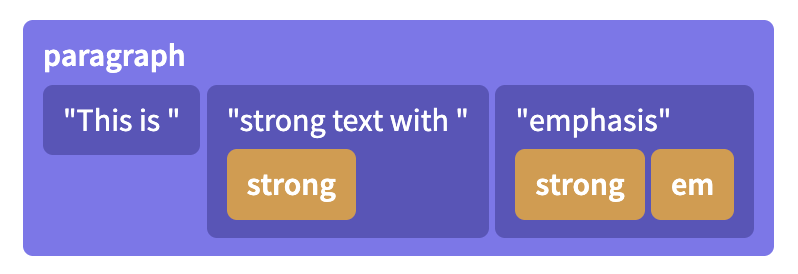

This is a lot like the browser DOM, in that it is recursive and tree-shaped. But it differs from the DOM in the way it stores inline content. Whereas in ProseMirror, the inline content is modeled as a flat sequence, with the markup attached as metadata to the nodes.

Identity and persistence

In the DOM, nodes are mutable objects with an identity, which means that a node can only appear in one parent node, and that the node object is mutated when it is updated.

In ProseMirror, on the other hand, nodes are simply *values* that can appear in multiple data structures at the same time, it does not have a parent-link to the data structure it is currently part of. So it is with pieces of ProseMirror documents. They don't change, but can be used as a starting value to compute a modified piece of document. They don't know what data structures they are part of, but can be part of multiple structures, or even occur multiple times in a single structure. They are *values*, not stateful objects. This means that every time you update a document, you get a new document value. That document value will share all sub-nodes that didn't change with the original document value, making it relatively cheap to create.This has a bunch of advantages. It makes it impossible to have an editor in an invalid in-between state during an update, since the new state, with a new document, can be swapped in instantaneously. It also makes it easier to reason about documents in a somewhat mathematical way, which is really hard if your values keep changing underneath you. This helps make collaborative editing possible and allows ProseMirror to run a very efficient DOM update algorithm by comparing the last document it drew to the screen to the current document.

Data structures

The content of a node is stored in an instance of Fragment, which holds a sequence of nodes. Even for nodes that don’t have or don’t allow content, this field is filled (with the shared empty fragment).

Some node types allow attributes, which are extra values stored with each node. For example, an image node might use these to store its alt text and the URL of the image.

In addition, inline nodes hold a set of active marks—things like emphasis or being a link—which are represented as an array of Mark instances.

1 | import {schema} from "prosemirror-schema-basic" |

Each ProseMirror document has a schema associated with it. The schema describes the kind of nodes that may occur in the document, and the way they are nested. For example, it might say that the top-level node can contain one or more blocks, and that paragraph nodes can contain any number of inline nodes, with any marks applied to them.

Node Types

Every node in a document has a type, which represents its semantic meaning and its properties, such as the way it is rendered in the editor.

When you define a schema, you enumerate the node types that may occur within it, describing each with a spec object:

1 | const trivialSchema = new Schema({ |

Every schema must at least define a top-level node type (which defaults to the name "doc", but you can configure that), and a "text" type for text content.

Content Expressions

The strings in the content fields in the example schema above are called content expressions. They control what sequences of child nodes are valid for this node type.

For example "paragraph" for “one paragraph”, or "paragraph+" to express “one or more paragraphs”. Similarly, "paragraph*" means “zero or more paragraphs” and "caption?" means “zero or one caption node”. You can also use regular-expression-like ranges, such as {2} (“exactly two”) {1, 5} (“one to five”) or {2,} (“two or more”) after node names.

Such expressions can be combined to create a sequence, for example "heading paragraph+" means ‘first a heading, then one or more paragraphs’. You can also use the pipe | operator to indicate a choice between two expressions, as in "(paragraph | blockquote)+".

Some groups of element types will appear multiple times in your schema—for example you might have a concept of “block” nodes, that may appear at the top level but also nested inside of blockquotes. You can create a node group by giving your node specs a group property, and then refer to that group by its name in your expressions.

1 | const groupSchema = new Schema({ |

Here "block+" is equivalent to "(paragraph | blockquote)+".

It is recommended to always require at least one child node in nodes that have block content (such as "doc" and "blockquote" in the example above), because browsers will completely collapse the node when it’s empty, making it rather hard to edit.

The order in which your nodes appear in an or-expression is significant.

Marks

Marks are used to add extra styling or other information to inline content. A schema must declare all mark types it allows in its schema. Mark types are objects much like node types, used to tag mark objects and provide additional information about them.

By default, nodes with inline content allow all marks defined in the schema to be applied to their children. You can configure this with the marks property on your node spec.

1 | const markSchema = new Schema({ |

The set of marks is interpreted as a space-separated string of mark names or mark groups—"_" acts as a wildcard, and the empty string corresponds to the empty set.

Attributes

The document schema also defines which attributes each node or mark has. If your node type requires extra node-specific information to be stored, such as the level of a heading node, that is best done with an attribute.

1 | heading: { |

In this schema, every instance of the heading node will have a level attribute under .attrs.level. If it isn’t specified when the node is created, it will default to 1.

When you don’t give a default value for an attribute, an error will be raised when you attempt to create such a node without specifying that attribute.

Serialization and Parsing

In order to be able to edit them in the browser, it must be possible to represent document nodes in the browser DOM. The easiest way to do that is to include information about each node’s DOM representation in the schema using the toDOM field in the node spec.

Documents also come with a built-in JSON serialization format. You can call toJSON on them to get an object that can safely be passed to JSON.stringify, and schema objects have a nodeFromJSON method that can parse this representation back into a document.

Extending a schema

The schema-list module exports a convenience method to add the nodes exported by those modules to a nodeset.

Document transformations

Transforms are central to the way ProseMirror works. They form the basis for transactions, and are what makes history tracking and collaborative editing possible.

Steps

Updates to documents are decomposed into steps that describe an update. You usually don’t need to work with these directly, but it is useful to know how they work. Examples of steps are ReplaceStep to replace a piece of a document, or AddMarkStep to add a mark to a given range.

applying a step can fail, for example if you try to delete just the opening token of a node, that would leave the tokens unbalanced, which isn’t a meaningful thing you can do. This is why apply returns a result object, which holds either a new document, or an error message. You’ll usually want to let helper functions generate your steps for you, so that you don’t have to worry about the details.

Transforms

An editing action may produce one or more steps. The most convenient way to work with a sequence of steps is to create a Transform object (or, if you’re working with a full editor state, a Transaction, which is a subclass of Transform).

Rebasing

When doing more complicated things with steps and position maps, for example to implement your own change tracking, or to integrate some feature with collaborative editing, you might run into the need to rebase steps.

You might not want to bother studying this until you are sure you need it.

The editor state

What makes up the state of an editor? You have your document, of course. And also the current selection. And there needs to be a way to store the fact that the current set of marks has changed, when you for example disable or enable a mark but haven’t started typing with that mark yet.

Those are the three main components of a ProseMirror state, and exist on state objects as doc, selection, and storedMarks.

Selection

Selections are represented by instances of (subclasses of) the Selection class. Like documents and other state-related values, they are immutable—to change the selection, you create a new selection object and a new state to hold it.

Selections have, at the very least, a start (.from) and an end (.to), as positions pointing into the current document. Many selection types also distinguish between the anchor (unmoveable) and head (moveable) side of the selection, so those are also required to exist on every selection object.

Transactions

State updates happen by applying a transaction to an existing state, producing a new state. Conceptually, they happen in a single shot: given the old state and the transaction, a new value is computed for each component of the state, and those are put together in a new state value.Transaction is a subclass of Transform, and inherits the way it builds up a new document by applying steps to an initial document. In addition to this, transactions track selection and other state-related components, and get some selection-related convenience methods such as replaceSelection.

Plugin

When creating a new state, you can provide an array of plugins to use. These will be stored in the state and any state that is derived from it, and can influence both the way transactions are applied and the way an editor based on this state behaves.

Plugins are instances of the Plugin class, and can model a wide variety of features. The simplest ones just add some props to the editor view, for example to respond to certain events. More complicated ones might add new state to the editor and update it based on transactions.

When creating a plugin, you pass it an object specifying its behavior:

1 | let myPlugin = new Plugin({ |

The view componet

A ProseMirror editor view is a user interface component that displays an editor state to the user, and allows them to perform editing actions on it.

The definition of editing actions used by the core view component is rather narrow—it handles direct interaction with the editing surface, such as typing, clicking, copying, pasting, and dragging, but not much beyond that. This means that things like displaying a menu, or even providing a full set of key bindings, lie outside of the responsibility of the core view component, and have to be arranged through plugins.

Editable DOM

Browsers allow us to specify that some parts of the DOM are editable, which has the effect of allowing focus and a selection in them, and making it possible to type into them. The view creates a DOM representation of its document (using your schema’s toDOM methods by default), and makes it editable. When the editable element is focused, ProseMirror makes sure that the DOM selection corresponds to the selection in the editor state.

most cursor-motion related keys and mouse actions are handled by the browser, after which ProseMirror checks what kind of text selection the current DOM selection would correspond to. If that selection is different from the current selection, a transaction that updates the selection is dispatched.

Even typing is usually left to the browser, because interfering with that tends to break spell-checking, autocapitalizing on some mobile interfaces, and other native features. When the browser updates the DOM, the editor notices, re-parses the changed part of the document, and translates the difference into a transaction.

Data flow

Efficient updating

One way to implement updateState would be to simply redraw the document every time it is called. But for large documents, that would be really slow.

Since, at the time of updating, the view has access to both the old document and the new, it can compare them, and leave the parts of the DOM that correspond to unchanged nodes alone. ProseMirror does this, allowing it to do very little work for typical updates.

Commands

In ProseMirror jargon, a command is a function that implements an editing action, which the user can perform by pressing some key combination or interacting with the menu.

The prosemirror-commands module provides a number of editing commands, from simple ones such as a variant of the deleteSelection command, to rather complicated ones such as joinBackward, which implements the block-joining behavior that should happen when you press backspace at the start of a textblock. It also comes with a basic keymap that binds a number of schema-agnostic commands to the keys that are usually used for them.

When possible, different behavior, even when usually bound to a single key, is put in different commands. The utility function chainCommands can be used to combine a number of commands—they will be tried one after the other until one return true.

Collaborative editing

Real-time collaborative editing allows multiple people to edit the same document at the same time. Changes they make are applied immediately to their local document, and then sent to peers, which merge in these changes automatically.

Algorithm

ProseMirror’s collaborative editing system employs a central authority which determines in which order changes are applied. If two editors make changes concurrently, they will both go to this authority with their changes. The authority will accept the changes from one of them, and broadcast these changes to all editors. The other’s changes will not be accepted, and when that editor receives new changes from the server, it’ll have to rebase its local changes on top of those from the other editor, and try to submit them again.